Reading Fiction Can Be Fun, But It Isn’t Enough To Boost Achievement

Teenagers who read a lot of fiction do better on international reading tests, according to a recent study. But that doesn’t mean we can boost achievement just by encouraging kids to read more fiction.

It’s well established that kids who read a lot generally do better in school. But there hasn’t been much research on whether it matters what they’re reading. A recent study, drawing on data from over 250,000 15-year-olds in 35 industrialized countries, claims to have found a “fiction effect.” After controlling for a range of factors, the researchers found that students who read a lot of fiction for pleasure did significantly better on a standardized reading test than their peers who frequently read newspapers, magazines, nonfiction, or comic books. The test included not only passages drawn from fiction but also some nonfiction. The researchers speculated that the experience of reading novels develops students’ ability to sustain attention, allowing for reflection and deep thought rather than superficial skimming.

On the surface, the findings appear to support a widespread belief among teachers that just getting kids to spend time reading books of their own choice, often fiction, is the key to boosting reading ability and overall achievement. This is essentially the theory that undergirds our prevailing approach to reading instruction, with a couple of modifications. (One is that students need to be practicing comprehension “skills” and strategies while reading books of their choice. The other is that their choices must be restricted to books they’re presumed to be able to read easily on their own.) It’s certainly an alluring concept: learning can be not only effortless but totally pleasurable. Unfortunately, as evidenced by declining reading scores and a widening gap between higher- and lower-performers, the theory is seriously flawed.

As the authors of the recent study acknowledge, their data shows only correlation, not causation. Maybe teenagers who are avid fiction readers already have a greater capacity for sustained attention than their peers, and that explains why they’re able to lose themselves in a novel—and score higher on reading tests.

But let’s assume there is a “fiction effect.” Speaking as a former teenager who read a lot of novels, I would say kids in that category find reading largely effortless. The kids who don’t choose to read much fiction—or anything else except maybe comic books—probably find reading a struggle. Maybe they never got a chance to master the foundational reading skills that would enable them to read fluently and sound out unfamiliar words quickly. Maybe they haven’t had a chance to acquire the sophisticated general knowledge and vocabulary that would allow them to understand the words and concepts used in many novels. Maybe both.

That calls into question the researchers’ recommendation that we simply encourage young people to read fiction—especially “boys from disadvantaged socio-economic backgrounds,” who they say are least likely to read it. To be sure, all students should have an opportunity to read books of their choice, including fiction. But it’s going to be hard to convince those who struggle with reading to engage in that activity for “pleasure.” And even if they’re required to read a lot of books independently at school, it’s unlikely to significantly boost their reading ability. If kids read only simple text, they never get the chance to become familiar with the sophisticated vocabulary, syntax, and concepts that could enable them to understand increasingly complex text—no matter how much they read.

There’s one possible way around this problem: have struggling readers listen to more complex novels being read aloud by expert readers—like teachers. One small-scale study found that this approach enabled readers who were a year or more behind to make enormous progress. After just 12 weeks of listening to two novels being read at a fairly fast pace, those students made 16 months of progress on a comprehension test that included both fiction and nonfiction passages. (It made no difference, by the way, whether their teachers were trained in comprehension strategies.)

So whether or not there’s a “fiction effect,” we need to do more than encourage struggling readers to pick up a novel. We need to introduce them to the pleasures of reading by enabling them to listen to stories they can’t yet read easily on their own. We need to use the power of narrative to expand their knowledge of the world. And we need to prepare them to wrest meaning from text that doesn’t provide a storyline. Yes, that will involve effort. But that’s what real learning generally requires.

Want to Level Up Your Comprehension Teaching?

Student Comprehension Cards

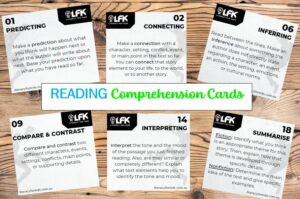

Are your students easily confused when reading texts on their own? Try using these critical thinking questions to scaffold their understanding.

You can use them with whole-class reads when students are asked to read a portion of the text independently. They also work well with independent reading programs, including literacy circle and book club models.

Older students need scaffolding when reading texts independently, and that scaffolding should come in various forms – not just annotation. When you use these turn-and-talk discussion task cards, you’ll get a better idea of what is confusing your students; therefore, you’ll be able to help them get back on track and comprehending the text more efficiently.

Reading comprehension strategies targeted in this product include predicting, connecting, summarizing, visualizing, inferring, questioning, analyzing, evaluating, and more.

Email us for your copy at info@literacyforkids.com.au

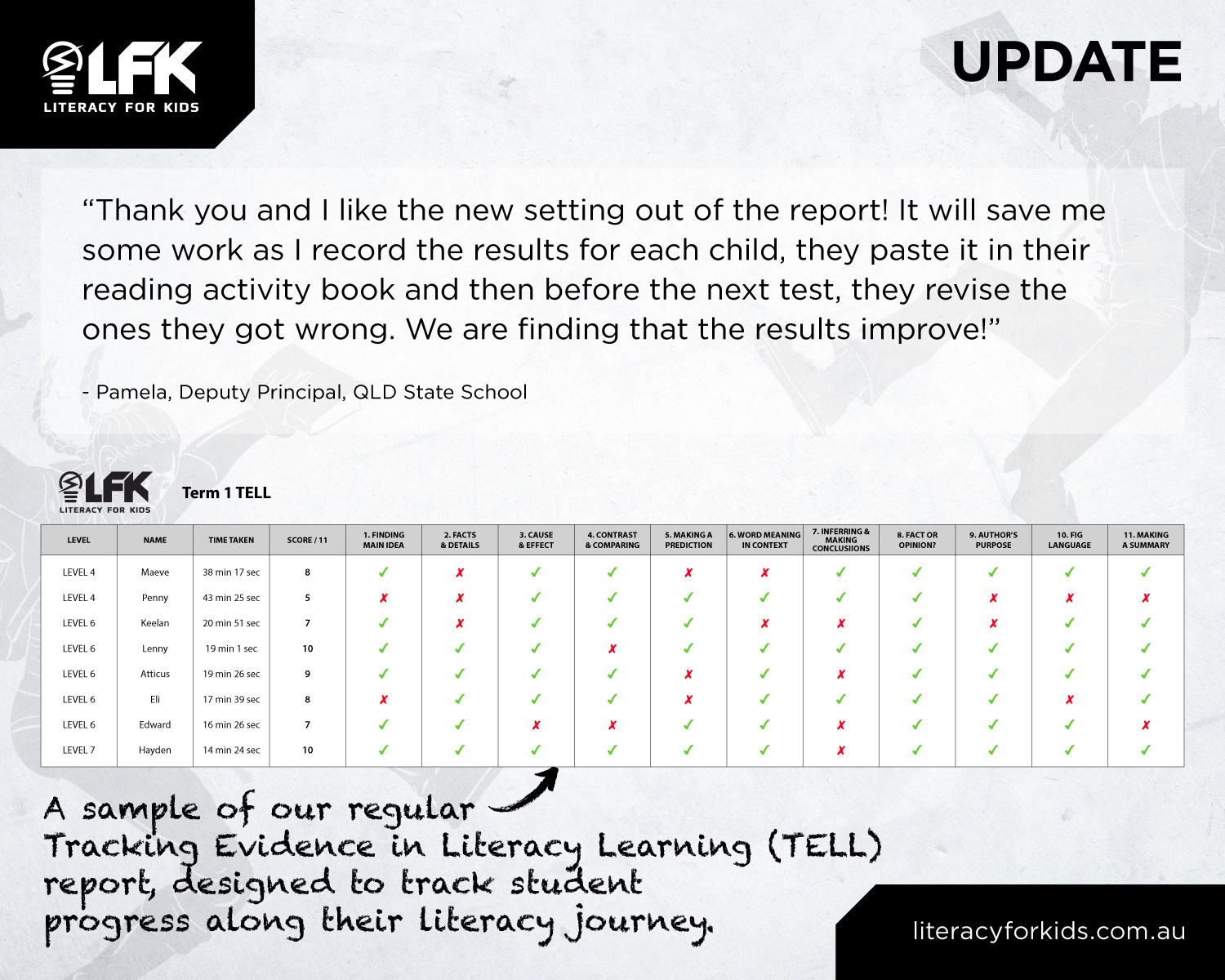

Attention Teachers: Indicators for Student Growth

In our discussions with educators, we found that they want tasks and measures to help assess the effectiveness of instruction, as well as clear criteria for mastery. This is why we created our latest report ~

This report helps you to better judge not only if students are making progress, but also the rate at which students make progress (term-by-term comparison).

The Reading Comprehension texts are at the appropriate level and complexity that the student can read independently and show 11 specific comprehension skills/strategies.

A successful literacy program’s content must be aligned with literacy outcomes. Literacy for Kids guarantees that your students work through engaging, quality content that focuses on essential skills in the core strands of literacy.

A successful literacy program’s content must be aligned with literacy outcomes. Literacy for Kids guarantees that your students work through engaging, quality content that focuses on essential skills in the core strands of literacy.LFK is a valuable teaching tool tailored to the needs, strengths, and interests of students. This is what sets our program apart – rich, engaging literacy experiences that gets results.

Literacy for Kids is currently in 250+ schools around Australia and NZ – and growing!

Contact us for your free trial and see how we can work with your school to improve literacy.

Our literacy programs have created the reading content to support your teaching. STEM, history, creative writing, science: with hundreds of kid-centric topics to choose from, our programs have been proven to lift literacy in schools and at home. Contact us today.

Confirmed Results!

An effective reading program needs to be backed by strong results. Literacy for Boys was independently tested in one of the largest State Primary schools in Qld. Students in Years 3 to 6 improved their reading, spelling and comprehension ages by an average of 12 months after only 18 weeks on our program! Click here for the full report.

Contact us if you’d like to trial Literacy for Boys or Literacy for Kids in your school.

info@literacyforboys.com.au

info@literacyforkids.com.au

Want your students to finish strong in their literacy? Want more from your literacy program? Contact us for a 30-day free trial in your school or classroom. New schools receive these great ‘Turn and Talk’ comprehension cards for their classroom ~

Check out our blogs for more ideas and tips.

7 Ways to Identify and Build a Student’s Capabilities

Literacy for Kids scores 100% improvement in reading skills with Year 6 Cohort

5 Ways to Build Student Confidence

Identify Comprehension Gaps with these great cards

Steps to Successfully Support Disengaged Learners

See us featured in The Educator Australia magazine

Research confirms that early reading boosts literacy

Boys Love LFB – Here’s what they have to say!

Get boys reading in the digital age

Why write? Tips for reluctant writers

Brought to you by Tanya Grambower